|

|

|

| DEATH:

1682 RUISDAEL |

| ^

Born on 14 March 1836: Jules-Joseph

Lefebvre, French Academic

painter who died on 24 February 1911. — Lefebvre studied under Leon Cogniet, and afterwards at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1861. His early works were based upon historical events. However, after the death of close family members in the mid 1860s he began to specialise in painting nudes, such as Chloe. Lefebvre became a professor of the Académie Julian in Paris in the 1870s. The Belgian Symbolist painter Fernand Khnopff numbered amongst his students. Lefebvre received many awards during his long life, including being made Commandeur of the Légion d'honneur in 1898. — LINKS — Flora — Girl with a Mandolin — Mary Magdalen in the Grotto — Ophelia — Truth — The Language of the Fan (1882) — Chloé (1875) _ This is perhaps the most famous, notorious, well loved, well hung and controversial painting in Australia. Chloé was exhibited to great popular acclaim winning gold medals in the Paris Salon in 1875, the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879 and the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880. She was purchased in 1882 by a surgeon, Thomas Fitzgerald (later Sir Thomas) and subsequently loaned to the National Gallery of Victoria. In 1883, after three weeks of exhibition, she fell victim to Victorian "wowserism" (puritanical fanaticism) when outraged citizens objected to seeing the naked female form displayed on the Sabbath. Upon the death of Sir Thomas in 1908, Chloé was purchased by Henry Figsby Young, an ex-digger turned hotel proprietor, for the very considerable sum of 800 pounds. One story relates that Henry took the painting back to his home above Young and Jackson's Hotel and hid it from his wife. While he was away and she was "spring cleaning", the irate wife discovered it and banished it to the public bar, which ironically turned it into a smash hit. It has remained there ever since, apart from touring Australia to raise funds for the Red Cross during World War I and being loaned as the centre-piece for the exhibition "Narratives, nudes and landscapes" at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1995. As for the model "Chloé", she had posed for the painting when she was 19, had subsequently fallen in love with Jules Lefebvre and when the artist married her sister, she was devastated. She boiled up phosphorous match-heads, drank the poisonous concoction and died tragically, at 21. Or so they say! |

| ^

Died on 14 March 1682: Jacob

Isaakszoon van Ruisdael (or Ruysdael), Dutch painter specialized

in Landscapes

born in 1628 or 1629, nephew of Salomon

van Ruysdael. — LINKS — Bentheim Castle (mega-image) — another Bentheim Castle (1653) _ During the years from about 1650 to about 1655, the heroic quality of Ruisdael's landscapes increases. The forms become larger and more massive. Giant oaks and beeches as well as shrubs acquire an unprecedented abundance and fullness. Colors become more vivid, space increases in both height and depth, and there is an emphasis on the tectonic structure of the compositions. He strove to achieve heroic effects without sacrificing the individuality of a single tree or bush. An outstanding example of this tendency is his mighty view of Bentheim Castle. Ruisdael visited Bentheim, a small town in Wesphalia near the Dutch-German border, when he travelled to the region with his friend Berchem in the early fifties. Bentheim's castle is, in fact, on an unimposing low hill, but in his painting Ruisdael enlarged it into a wooded mountain providing the castle with a commanding position. His invention is a superb expression of his aggrandizement of solid forms during this phase. The dense mass of the mountain, obliquely stretching away into depth, and the coulisses on either side of the front edge of the painting are reminiscent of compositional schemes used by the generation of his teachers, but the spatial clarity is new, as are the strong colors, the energy of the brushwork, and the way he unifies the close view of a nearly overwhelming wealth of detail with the most distant parts of the landscape into a consistent whole. The impact of the broad prospect is as intense as the vegetation seen close up. Ruisdael continued to include Bentheim Castle in his landscapes, seen in various settings and from different viewpoints, until his very last years. —and another The Castle at Bentheim (1651, 98x81cm) _ Jacob van Ruisdael, the greatest of all Dutch seventeenth-century landscape painters, was born in Haarlem. He was a member of a dynasty of artists and was trained in the studios of his father, Isaac Jacobszoon van Ruisdael and his uncle, Salomon van Ruysdael. Salomon worked in the 'monochrome' Haarlem style of which Jan van Goyen and Pieter Molijn were also practitioners, and Jacob's earliest paintings display a powerful debt to his uncle's work. He joined the Haarlem guild in 1648 and two years later travelled with his friend Nicolaes Berchem (1620-1683), a painter of Italianate landscapes, to the German border. There, they visited Bentheim, a small town in Westphalia on the border between the United Provinces and Germany. They both sketched Bentheim Castle and later worked up their drawings into paintings. Indeed Ruisdael, whose imagination was particularly inspired by Bentheim, made a whole series of paintings of the castle perched dramatically on an outcrop of rock. Ruisdael's and Berchem's views of Bentheim provide a fascinating comparison between the two artists and their approach to landscape: whereas in a painting of 1656 Berchem turned the castle into a fairy-tale cluster of pinnacles and placed it in the shimmering distance behind a scene of carefree Italian peasants watering their cattle, Ruisdael transformed the low hill on which the castle sits into a sheer cliff, topped by a granite fortress. — Landscape with Waterfall (mega-image) — Mountainous Landscape with Waterfall (mega-image) — The Windmill at Wijk-bij-Duurstede (mega-image) _ The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede (1670, 83x101cm) _ A Dutch landscape consists essentially of sky dominating low-lying land, where water (whether it be the sea or some canal) frequently reflects the clouds. In the work of Ruisdael the feeling of infinity, in which man seems lost, attains a Pascalian gravity. In this painting the sky responds in its cloud formations to the mighty wings of the windmill. As in Rembrandt's mature phase, which is approximately contemporaneous, this landscape shows classical elements which strengthen the compositional power. Horizontals and verticals are coordinated with the Baroque diagonals, which are still alive and help to create a mighty spaciousness. The atmospheric quality is as important as ever in uniting the whole impression. Light breaks now with greater intensity through the clouds and the clouds themselves gain in substance and volume. The sky forms a gigantic vault above the earth, and it is admirable how almost every point on the ground and on the water can be related to a corresponding point in the sky. _ detail _ In this painting the sky responds in its cloud formations to the mighty wings of the windmill. — View of Haarlem (mega-image) — Water mill (mega-image) — Rough Sea (1670) — Wheatfields, detail — The Great Forest. |

| — The

Great Oak (1652) _ The painting is signed and dated, however, in the

18th century it was wrongly attributed to Nicolaes Berchem. In fact Berchem

painted only the staffage figures of the picture. — Landscape with a House in the Grove (1646, 105x162cm) _ Ruisdael is one of the exceptional painters who appears on the scene as a precocious complete master. He was active as an independent artist before he was inscribed as a member of the Haarlem guild in 1648. More than a dozen of his works are signed and dated 1646, when he was a seventeen- or eighteen-year-old teenager, and in the following year the number increases. In these early works there is no fumbling or groping. On the contrary, from the beginning he surpasses his models by his ability to enlarge a detail of nature into central motif. The sand dunes and clumps of trees around his native town which were his favourite subjects during these years are rendered with loving care and from the moment we recognize his hand until his last years he gave unprecedented meticulous attention to arboreal details. He was the first artist to depict a variety of trees that are consistently and unequivocally recognizable to the botanist on account of their overall habit. — View of Amsterdam (52x43cm) _ The painting depicts the bank of the Binnenamstel, in the background the tower of the Zuiderkerk. _ detail — View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds (1665, 62x55cm) _ Of about the late 1660s are many firsthand views of the Dutch landscape in its various aspects by Ruisdael. The sea, the shore, the vast fertile plains now become important subjects side by side with the woods and waterfalls, and they are always seen under a majestic sky. In his panoramic views of Haarlem with its bleaching grounds, which continue into the seventies, the master's hand is felt in the strength and deceptive simplicity of the compositions. Bleaching fields were familiar sights in his time. After brewing, bleaching linen manufactured in Holland and unbleached cloth imported from England, Germany, and the Baltic countries was Haarlem's major industry. Jacob's 'Haarlempjes' — as they were called in his day — appeal to us because they offer what is now accepted as the most characteristic view of the Dutch countryside while achieving an unparalleled degree of openness and height. The one at Zurich, a summit of Jacob's achievement, is an exemplar of the type. Its sky, as the skies in most of them, takes up more than two thirds of the canvas, but the impression of height is increased here by the vertical format, and still more by the dominant part the towering, strongly modelled clouds play in the awe-inspiring aerial zone. The prospect of the plain is shown from an exceptionally distant and elevated point of view. As a result there is a reduction in both in scale and in overlappings of the watery dunes, woods, and tracts of land. The firm cohesion of the great cloudy sky gains in mass and significance from its relations to the diminutive forms. The eye can explore here - more than in most other 'Haarlempjes' - the vast expanse of the land richly differentiated by the gradations of alternating bands of light and shadow into the distance toward a horizon stretched taut as sinew. — Two Water Mills and an Open Sluice (1653) _ Besides the Bentheim Castle, another motif Ruisdael discovered on his trip to the Dutch-German border region was the water mill. The half-timbered overshot and undershot mills he favoured were found in the eastern provinces of the Netherlands and in the area near Bentheim. Of course, earlier artists included water mills in their pictures but he was the first to make them the principal theme of a painting. The subject became one of the specialities of his pupil Meindert Hobbema, and today, when we think of them, his paintings not Ruisdael's come to mind. But in judging their respective accomplishments it is helpful to recall that Ruisdael painted powerful ones, such as Two Water Mills and an Open Sluice, which impresses by the cohesion of its forms and clear daylight effect, before Hobbema held a brush in his hand. — The Hunt (107x147cm) _ The animals were painted by Adriaen van de Velde. — The Jewish Cemetery (1660) — another The Jewish Cemetery (1657, 141x183cm) — Ruins sometimes play a prominent role, and gloomy skies set a melancholy mood. Ruisdael's rare ability to create a compelling and tragic mood in nature is best seen in his famous Jewish Cemetery of 1660. The autograph 1657 version is larger and more elaborate. These works are moralizing landscapes that were painted with a deliberate allegorical programme. The combination of their conspicuous tombs, ruins, large dead beech trees, broken trunks, and rushing streams alludes to the familiar themes of transience and the vanity of life and the ultimate futility of human endeavor, while the burst of light that breaks through the ravening clouds in each painting, their rainbows and the luxuriant growth that contrasts with the dead trees offer a promise of hope and renewed life. |

|

The masterliness of the 1660 painting lies in the artist's clear and concentrated

presentation of these ideas. The eye focuses on the three tombs in the middle

distance, where the light is centralized. They present a truthful picture

of the actual, identifiable sarcophagi as they can still be seen in the

Portuguese-Jewish Cemetery at Ouderkerk on the Amstel River near Amsterdam.

Ruisdael made carefully worked-up drawings of the tombs, one of which he

used as a preparatory drawing for the paintings. But the landscape settings

of the paintings bear no resemblance whatsoever to the site at Ouderkerk.

They are Ruisdael's inventions. The cemetery never had monumental ruins.

Those seen in the Dresden version were transplants from the shattered remains

of Egmond Castle near Alkmaar, a site about forty kilometers from Ouderkerk;

they also are based on a preparatory drawing. The ruins seen in the Detroit

painting are probably derived from the ruins of Egmond's old Abbey Church.

A rushing stream does not bisect the actual burial ground. (Would anyone

in his right mind place tombs near a vigorous stream which would wreak havoc

with the tombstones and coffins beneath them when it flooded?). The stream

was included as a traditional allusion to the passage of time. Most remarkable

is the barren beech tree in the 1660 picture that gestures toward the three

tombs and heavenwards. If ever a tree was capable of seducing a viewer to

accept the pathetic fallacy of endowing natural forms with human feelings

and emotions it is this dead beech. The iconographical programme of Ruisdael's two versions of the Jewish Cemetery leaves no doubt that they were intended as moralizing landscapes. He made no others that can be given a similar unmistakable reading. None of his other existing paintings include tombs; those done by his contemporaries are rare, and some of them are based on his depictions of the sarcophagi at Ouderkerk. However, Ruisdael made numerous pictures that include identifiable or imaginary ruins, dead and broken trees, rushing streams, rivers, and waterfalls. Were these motifs invariably intended by the artist as symbols of transience and the vanity of life, and does the handful of them that include rainbows allude to hope? It has been argued that this is indeed the case, and that these motifs not only offer the iconographical essence of Ruisdael's landscapes but offer the key to the meaning to seventeenth-century landscape painting. According to this interpretation they were intended as visual sermons to convey the biblical message that man lives in a transient world beset by sinful temptation, but may hope for salvation. — Landscape with Church and Village (1670, 59x73cm) _ In the late 1660s, perhaps inspired by the example of Philips Koninck, Jacob van Ruisdael painted a number of extensive landscapes, of which this is a fine example. Like Koninck, he adopts a high viewpoint, devoting more than half the canvas to a cloud-filled sky. It has been suggested that the church in the centre is that of Saint Agatha at Beverwijk, about seven miles north of Haarlem, where Ruisdael lived and worked. The tower of that church, however, was different and in any case it is unlikely that Ruisdael was attempting topographical accuracy. The painting was no doubt based on drawings made in the vicinity of Haarlem which Ruisdael then took back to his studio and transformed into an imaginative landscape. There are four other landscapes by Ruisdael which show the same view or part of the same view with small differences of detail. — The Marsh in a Forest (1665, 72x99cm) _ Among Ruisdael's most personal creations are his large forest scenes of the sixties. In the Marsh in a Forest of about 1665 at the Hermitage powerful trees form a mighty group around a lonely pond. The decayed ones speak with their winding branches as vividly as those in full growth. There is more spaciousness now than there was in the earlier phase of the fifties. Massive trees no longer virtually seal off middle and background vistas. One can look into the distance under the trees, and the sky plays a more pronounced role. There is air all round, and the local colour, which was very distinct in the bluish green of the fifties, is somewhat neutralized by a greyish tint in the bronze-brown foliage. In this particular picture Jacob van Ruisdael based his composition on a design of Roelandt Savery which was accessible through the engraving of Egidius Sadeler. Yet the transformation of the Mannerist's work into his heroic terms is more significant than the dependence on it. Ruisdael did not accept the bizarre and ornamental play with nature's forms. He created an archetype of the splendour and grandeur of nature. |

| — An

Extensive Landscape with a Ruined Castle and a Village Church (1672,

109x146cm) _ Panoramic views of the flat plains in Holland are often said

to be the most distinctive contribution of Dutch landscape painting. They

differ from the 'world panorama' of earlier Flemish art by seemingly recording

the momentary view of a single scene, rather than being composed of a collection

of separate visual memories. Formally, they are characterized bb a low horizon

line, implying a low viewpoint. Although Ruisdael, perhaps the greatest

and the most versatile Dutch landscape specialist, did not invent this type

of picture, he became one of its most distinguished practitioners. This

painting may represent a view in Gooiland, a district to the east of Amsterdam;

there are, however, at least four other, smaller landscapes by Ruisdael

that show the same view or part of it with considerable variations, and

it is clear that he was not attempting strict topographical accuracy. Despite

the pretence of spontaneity, this work, like all landscape paintings of

the time, is a synthetic product of the artist's studio. Its dominant feature

is the sky, to which two thirds of the picture surface is devoted and which

is also reflected in the water of the foreground. This is the real, moisture-laden

sky of Holland billowing with clouds, the sun breaking sporadically through

scattering shafts of light across the countryside - effects which Constable

was later to emulate. Almost more remarkable than the truthful record of

the shape, density and illumination of the clouds is the illusion that they

are moving through space and over our heads (we tend to think that perspective

does not govern cloudscapes, but these seem to taper towards the horizon

and broaden at the upper edge of the painting). The long horizon too seems

to extend beyond the frame, broken only by church spires and the tiny white

sails of a windmill. But our sense of inhabiting the landscape is compromised

by our viewpoint in relation to the foreground. By letting us look down

into the bastion standing below the horizon line, the painter suggests that

we are viewing it from some improbably high place, higher also than the

shore on which the peasants graze their flock (both figures and animals

were painted by Adriaen van der Velde, a division of labour quite common

in Dutch landscapes). This implied detachment, however, strengthens the

elegiac mood aroused by the sight of overgrown ruins, melancholy reminders

of a distant and more heroic past. — Landscape with Waterfall (1670, 101x142cm) _ This is one of Ruisdael grandest landscapes. After Ruisdael had settled in Amsterdam about 1656-57 his compositions broaden, and a certain heaviness in the foreground disappears. The opening of the view suggests that he was impressed by Philips Koninck's panoramic views, but the fresh atmospheric effect, the brilliant glittering daylight which brightens the landscapes, the reflections, and vivid colours in the shadows are completely personal. In the late fifties Ruisdael also began to represent waterfalls in mountainous northern valleys, and in the sixties they became an important theme in his oeuvre. This motif was popularized by Allart van Everdingen after he returned to Holland in 1644 from a trip to Norway and Sweden, and Ruisdael, who never visited Scandinavia, derived his torrential falls in northern landscapes from Everdingen's art. — Waterfall by a Church (1670, 109x132cm) _ Ruisdael often chose waterfalls as a subject for his landscape paintings after the 1650s, inspired by the dramatic Scandinavian waterfall scenes of Allaert van Everdingen. Ruisdael's paintings were done in Amsterdam, which succeeded Haarlem as the centre of landscape painting after the middle of the century. At the same time a heightened expression became fashionable. — Waterfall in a Mountainous Northern Landscape (1665) _ After Ruisdael had settled in Amsterdam about 1656-57 his compositions broaden, and a certain heaviness in the foreground disappears. The opening of the view suggests that he was impressed by Philips Koninck's panoramic views, but the fresh atmospheric effect, the brilliant glittering daylight which brightens the landscapes, the reflections, and vivid colors in the shadows are completely personal. In the late fifties Ruisdael also began to represent waterfalls in mountainous northern valleys, and in the sixties they became an important theme in his oeuvre. This motif was popularized by Allaert van Everdingen after he returned to Holland in 1644 from a trip to Norway and Sweden, and Ruisdael, who never visited Scandinavia, derived his torrential falls in northern landscapes from Everdingen's art. — Wheat Fields (1675, 100x130cm) _ In Ruisdael's paintings of the 1670s, like this one, flat landscape subjects are characteristic, as are the converging lines of earth and sky and the alteration of shadow and sunlight. The tiny figures who populate Ruisdael's canvases - indeed, all human activities - are ultimately dwarfed by the vast canopy of sky and immense, towering clouds. This vision of nature is impressive and powerful yet never loses its wistful, melancholic beauty. — Winter Landscape (1670, 42x50cm) _ A survey of the large oeuvre of Jacob van Ruisdael reveals he painted virtually every subject depicted by Dutch landscapists: dunes and country roads, grainfields, panoramas, rivers and canals, woods and forests, ruins, winter scenes, water and windmills, city views, mountain scenes, Scandinavian landscapes, and seascapes and views of beaches as well. Ruisdael's winter landscapes are not the least remarkable in the oeuvre. In the first-rate example of one at Munich forbidding dark clouds hang over a forlorn snow-covered scene. There is no trace here of the gaiety of Avercamp's better known winterscapes and, unlike his, Ruisdaele's conjures up no image of skaters and other delights of the season. Its subject is a rarer one: the brooding mood of a winter day darkened by threatening clouds. — 11 prints at FAMSF |

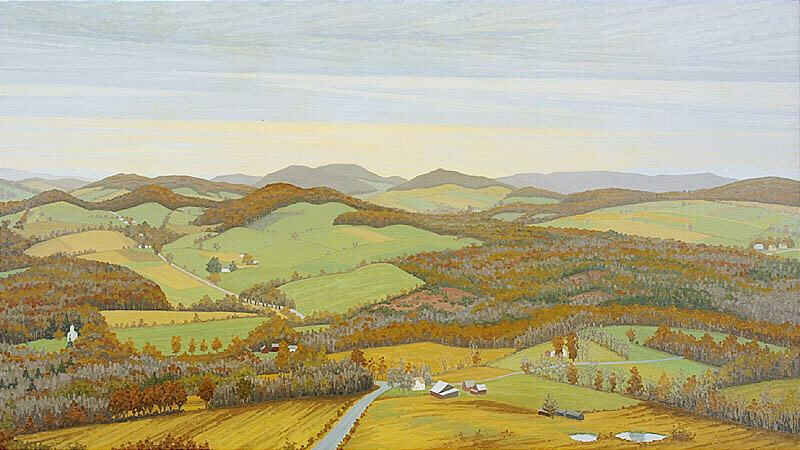

| ^

Born on 14 March 1892: John

Fulton “Jack” Folinsbee, US artist who died on

10 May 1972. — Born in Buffalo, died in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Jack Folinsbee came to New Hope in 1916 at the suggestion of tonalist painter Birge Harrison. Primarily known as a landscape painter, he also did portraits. His early impressionist landscapes employ light colors. Following a 1926 trip to France, Folinsbee began to use darker, brooding colors, and his work became more expressionist in approach. Known for his paintings of shad fish along the Delaware River in Lambertville, the painter also depicted the factories around his home and the Maine seacoast. Under Folinsbee's brush subjects that would not rise above the commonplace with lesser artist become beautiful and powerful. The factory, with its dull red walls, a flash of green water, gray smoke stacks and rolling clouds of smoke, epitomizes the spirit of iron and steel. Above all, it has splendor that does not depend on what we are accustomed to consider beauty." — John Fulton Folinsbee attended the Gunnery School, Connecticut, 1907-11, Art Students League Summer School, Woodstock, New York, 1912. Among those who taught him or influenced him are Birge Harrison, John Carlson, Frank Vincent DuMond, Robert Spencer Giotto, Masaccio, El Greco, Paul Cézanne, George Bellows, George Luks. John Folinsbee lived in New Hope from 1916 to 1972. He and his wife, Ruth, moved to New Hope upon the suggestion of Birge Harrison, who had several friends in the flourishing artists' colony. Ruth Folinsbee was involved with the founding of the Philips Mill Association, which brought people together for art exhibitions, theater performances, and social gatherings. She also was one of the original subscribers and stockholders of the Bucks County Playhouse in 1939. John Folinsbee chaired the Art Committee for the Philips Mill Association in 1930. Along with Edward Redfield, Daniel Garber, Lloyd R. Ney, and writer Henry Chapin, John Folinsbee formed the New Hope Scientific Society, a social group which gathered for evening games of poker. Harry Leith-Ross was a close friend from his Woodstock School days, who acted as best man at Folinsbee's marriage to Ruth Baldwin on 10 October 1914. Other colleagues in New Hope included William Lathrop and Robert Spencer. Folinsbee was very close to his son-in-law, Peter G. Cook, also a fine artist. |

-

-